Latest posts

- Journal article: Reimagining Peace Education in Nepal: Arts-Based, Learner-Centric Pedagogy for Social Justice and Equity 13 July 2025

- Curricula: Mithila art-focused local curriculum in Nepal 2 July 2025

- MAP International Online Conference 2025 1 June 2025

- Policy brief: Gira Ingoma book and policy brief: “The Culture We Want, for the Woman We Want” 28 November 2024

- Manuals and toolkits: GENPEACE Children’s Participation Module in the Development Process 13 November 2024

- Journal article: [Working Paper] Gira Ingoma – One Drum per Girl: The culture we want for the woman we want 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Beyond Tradition: Psychosocial Model 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Beyond Tradition Module: Revitalizing Lenong as a Model for Teaching Betawi Arts 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Beyond Tradition: Lenong Revitalisation as a Model for Teaching Betawi Cultural Arts 30 October 2024

- Beyond Tradition Lenong Performance “RAWR…! Kite Kagak Takut” 30 October 2024

- Journal article: [Working Paper] Facing Heaven – Déuda Folklore & Social Transformation in Nepal 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Building Community Curriculums 24 October 2024

Making connections: reflections on the use of proverbs in research and practice

23rd March 2020

This post was originally published via Changing the Story on 19th March 2020. Changing the Story is an AHRC GCRF project which asks how the arts, heritage and human rights education can support youth-centred approach to civil society building in post-conflict settings across the world. The development of the MAP project was a major output of Changing the Story and the two projects continue to work closely together. Find out more about Changing the Story and see the original post here: https://changingthestory.leeds.ac.uk

Written by Chaste Uwihoreye and Kirrily Pells, in collaboration with Eric Ndushabandi and Ananda Breed.

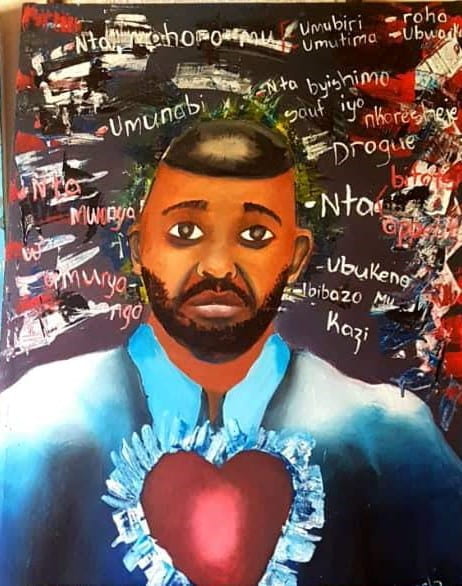

A common trope oft repeated in the wake of horrific events is that the ensuing pain is inexpressible or that certain stories cannot be told. In the case of Rwanda following the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi which saw between 800,000 and a million people killed in the space of 100 days, similar assumptions are also frequently deployed. One of us (Kirrily) recalls on her first visits to the country, being told mainly by other ‘outsiders’, but also by some Rwandans, that “Rwandans don’t talk”. However, as collaborator Chaste, a psychologist and Country Director of Uyisenga Ni Imanzi observes through his own work: Rwandans are talking all the time. Numerous Rwandan proverbs allude to the ways in which it is said that Rwandans may share information either briefly or even through silence and indeed it is those who do not understand what is being conveyed that say Rwandans do not talk. For example, “siko kumva, ubwira uwumva ntavunika” roughly translating as ‘to speak a lot does not make for more understanding’ or “ucira injiji amarenga amara ibinonko” meaning that you can use many gestures to talk with someone but if they are not aware of these gestures, you end up being tired. This instead challenges us as researchers and practitioners to better attend to the multiple ways in which people express their stories and crucially challenges us on how we might listen. Within our project Connective Memories: intergenerational expressions in contemporary Rwanda, on which we collaborate with Dr Eric Ndushabandi from the Institute of Research and Dialogue for Peace and Professor Ananda Breed from the University of Lincoln, we are working together with 10 young people and 6 adults as co-researchers on a participatory action research (PAR) project on the theme of isangizanyankuru. Isangizanyankuru was chosen by the group as a Kinyarwandan concept akin to memory but avoiding the more direct translation Kwibuka (meaning to remember) which is closely associated with the official commemoration of the Genocide. Participants noted that isangizanyankuru encompassed a sense of connection, between the individual and the collective and between past, present and future, with an emphasis on sharing through multiple modes of expression. Connective Memories works in collaboration with Mobile Arts for Arts to adapt arts-based methods to research.

One of the research questions for the project created by the co-researchers speaks to these concerns on listening to multiple forms of expression and asks ‘how do we respect the memories of others?’ In exploring this question, one emerging finding is the value and significance of proverbs both as a means of expressing one’s story and in listening to one another. In Rwanda, proverbs (imigani in Kinyarwanda) are “often used to express what a person has seen, heard and experienced at the level of emotions, feelings and states of mind, as well as to indicate to someone that they have been understood” (Bagilishya, 2000). As a Rwandan proverb states: “akari kumutima gasesekara ku munwa” meaning what you believe, think and feel has to be expressed externally by talking, actions, behaviours and attitudes. The Kinyarwanda word imigani therefore expresses the notion of a conversation or a dialogue, attempting to elicit “a mode of expression used to recognize, confirm and participate in what the other is living on an emotional level” (Bagilishya, 2000). In this sense, connectivity is at the heart of both isangizanyankuru and imigani so making the latter an interesting mode through which to explore the former. This approach really resonated with research participants. In an end of day reflective exercise where participants were asked which moment from the day they were going to take away with them, many repeated one of the proverbs that had been shared during the day and which had spoken to them.

Rwandan proverbs with their rich metaphorical language drawing on a rich repertoire of cultural symbolism therefore are an important mode of expression through which it is possible to express one’s own story or memories. During story circle, part of the Mobile Arts for Peace methodology, which the team drew upon for the Isangizanyankuru project, participants are asked to share a story which illustrated a conflict in the community which they would like to resolve. Participants’ memories and stories are often peppered with proverbs as a means of conveying multiple truths, such as “utaganiriye na se ntamenya icyosekuru yasize avuze” meaning when you do not talk with your father, you cannot know what your grandfather said before dying. This can be interpreted literally in the sense of regret at lack of family communication, but takes on particular significance in the Rwandan context and the often near absence of entire generations within families as a consequence of genocide. We have also used proverbs to help frame sessions focused on the sharing of memories and story. Proverbs such as “Ikinu kibi kibaho ni ukubwira utakumva” meaning something that is hurtful is to talk to someone who is not interested or “kubwira utakumva ni nko guta inyuma y’umusozi wa huye” meaning to speak to someone who is not interested is like the rain in Huye forest.

We have observed that proverbs facilitate a potentially transformatory encounter. Proverbs remind us that the person telling the story is the expert of their own life: “Ntiribara umukuru nk’umuto waribonye” (means that adults cannot explain better an event than the young person who has experienced it) is particularly pertinent for a project like Changing the Story, which aims to challenge adult-child power relations and foreground the stories of young people. The expression of a proverb after a story has been told, is a means of expressing an appropriate emotion, so honouring the person and the story – respecting the memories of others, to answer the question posed by the young people. This is important whether in the context of a research interview or therapeutic practice. As well as being an object of research therefore, we suggest that proverbs may be a way to research, as a mode of communication, as a way to build trust and empathy and as a means of exploring the multiple layers of experience: “Umugani Ugana Akariho” – the proverb reflects reality.