Latest posts

- Policy documents: UNICEF Innocenti Discussion Paper on Children and Youth Participation (August 2025) 26 August 2025

- MAP International Online Conference 2025: Session Summaries Report 24 July 2025

- MAP 2025 Conference Highlights: Recordings and Slides 23 July 2025

- Journal article: Reimagining Peace Education in Nepal: Arts-Based, Learner-Centric Pedagogy for Social Justice and Equity 13 July 2025

- Curricula: Mithila art-focused local curriculum in Nepal 2 July 2025

- MAP International Online Conference 2025 1 June 2025

- Policy brief: Gira Ingoma book and policy brief: “The Culture We Want, for the Woman We Want” 28 November 2024

- Manuals and toolkits: GENPEACE Children’s Participation Module in the Development Process 13 November 2024

- Journal article: [Working Paper] Gira Ingoma – One Drum per Girl: The culture we want for the woman we want 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Beyond Tradition: Psychosocial Model 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Beyond Tradition Module: Revitalizing Lenong as a Model for Teaching Betawi Arts 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Beyond Tradition: Lenong Revitalisation as a Model for Teaching Betawi Cultural Arts 30 October 2024

Allow me to return home: get more love, care, and support when I’m bleeding

26th April 2023

Author

Juhi Adhikari

Youth Advisory Board member, Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) Participatory arts-based international research project in the UK, Rwanda, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, and Nepal.

Credit: Problem Image, Shony Bhatta (anonymised), 14-year-old, Female, Nepal

“Please allow me to return home; I’m scared to go to sleep with the cattle nearby. It’s just that I’m going through a normal procedure called menstruation, said 14-year-old Shony Bhatta to her father. “Don’t treat me as unclean, I don’t deserve this.”

In Nepal, the menstruation taboo is a social stigma that considers women and girls unclean or impure during their periods. This is especially true in the far-western and Himalayan regions, and this taboo is called Chhaupadi. Chhaupadi means that women and girls must sleep in isolated huts or sheds outside their homes during menstruation. They are also forbidden from touching other people, animals, plants, water sources, or religious icons. This practice exposes them to health and safety risks, such as infections, snake bites, cold weather, sexual assault, or even death. There are many efforts to end Chhaupadi and promote menstrual health and hygiene in Nepal. The government banned Chhaupadi in 2005 and made it a criminal offense in 2017. Many NGOs and activists are also working to raise awareness, educate communities, distribute sanitary pads, and challenge cultural norms. However, there are still many challenges and barriers to overcome this deeply rooted tradition.

Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) is a participatory arts-based research project which facilitates young people in Nepal, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, and Rwanda to explore the social issues that they believe create localized conflict in their communities and advocate for policy changes to solve the problems. In Nepal, as part of our research project, a group of teenage girls went to several schools and facilitated sessions with other teenage girls to share their perspectives and understand the social issues they are facing in a welcoming space. Many teenage girls raised the issue of ‘untouchability’ as a big concern, and stress for them, and they want to solve this social problem.

In the first drawing, I, Juhi Adhikari, a member of the Youth Advisory Board (YAB) from Nepal, show a reflection from one of the youth discussion sessions on how menstruation is still stigmatized in the Western region of the country. Some people in this region are seen to be very strict regarding their culture of “Chaupadi”. Due to the cultural stigma attached to being “impure” during menstruation and soon after childbirth, females are required to live away from home in a cramped, dangerous shed. As a young child who doesn’t even know how to take care of her personal hygiene and has blood stains all over her skirt and rashes over her thighs, Shony Bhatta is seen in this photo sobbing and pleading with her father to let her return home.

She considers it unreasonable that she had to stay out of school during menstruation, sleeps in a shed, and suffer a lot, simply because she was a girl and bleeding. Her mother, Sharmila Bhatta also feels helpless as she recalls how challenging it was for her to conceive Shony in a cowshed, and how she was forced to stay there with her newborn child for 11 days. She recalls the misery of being deprived of nourishing food and warm clothing to cover her daughter. She feels that Shony had no option but to submit as she looks at her daughter with a broken heart.

Her father, Dholu Bhatta, holds the belief that a girl or woman’s body is possessed by an evil spirit during menstruation and that this is why they should be kept away from the house and shouldn’t be fed nutritious food: doing so, according to their society, would strengthen the evil within them. The crops Shony touches would all die if she were allowed to walk around at this time, and she would poison every man she came into contact with. Even though he knows in his heart that this is wrong, he can’t go against the long-standing custom and asks his daughter to follow it instead. Shony is now forced to live alone.

She is now kept in isolation and is deprived of good quality food, sanitary conditions, independence, humanity, and dignity. While every female bleeds during her period, it is hardly ever positively recognized in the far western part of Nepal, despite being a natural process.

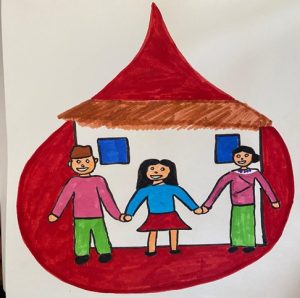

Credit: Solution Image, Shony Bhatta (anonymised), 14-year-old female, Nepal

“I used to assume that Chaupadi was an obligation, but after the awareness education campaign addressing menstruation, bodily autonomy, sex education, cleanliness, and sanitation in the programs and awareness campaign in the village for the youths, I learned that it wasn’t” stated Shony Bhatta.

As part of the discussion, we did not only talk about the social problems, we also explored the possible solutions from the teenage girl’s perspective. This second picture depicts the female voice and how they visualize solutions to make the world a better place to live for girls.

While a woman is menstruating, she may still live happily with her family in their home, as shown by the dark red blood drop in the background and the house inside it. This demonstrates that girls may live at home, receive extra care from their families, and consume nutritious food. The fact that the father and mother are wearing the same shade of clothing highlights their solidarity in supporting their daughter even while she is menstruating, and the shift in social attitudes that are taking place.

Dholu Bhatta moves forward while holding hands with his wife and his daughter. This illustrates how men and women may work together to transform society in ways that are advantageous to both genders. Shony and every other girl/woman like her in their society experienced embarrassment whilst menstruating and previously believed they’ll be treated cruelly and sent to a cowshed both during and after childbirth, while they were both experiencing these natural bodily processes.

Thus, it is very important to leave no one behind and ensure girls also have opportunities for thriving in their careers without any hindrances. The untouchability practice during the menstruation cycle is not only discriminatory but also a very stressful and mentally disturbing phase for many girls in Nepal. Without embracing natural bodily processes gracefully, our girls will not have a better place to live.