Latest posts

- Policy documents: UNICEF Innocenti Discussion Paper on Children and Youth Participation (August 2025) 26 August 2025

- MAP International Online Conference 2025: Session Summaries Report 24 July 2025

- MAP 2025 Conference Highlights: Recordings and Slides 23 July 2025

- Journal article: Reimagining Peace Education in Nepal: Arts-Based, Learner-Centric Pedagogy for Social Justice and Equity 13 July 2025

- Curricula: Mithila art-focused local curriculum in Nepal 2 July 2025

- MAP International Online Conference 2025 1 June 2025

- Policy brief: Gira Ingoma book and policy brief: “The Culture We Want, for the Woman We Want” 28 November 2024

- Manuals and toolkits: GENPEACE Children’s Participation Module in the Development Process 13 November 2024

- Journal article: [Working Paper] Gira Ingoma – One Drum per Girl: The culture we want for the woman we want 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Beyond Tradition: Psychosocial Model 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Beyond Tradition Module: Revitalizing Lenong as a Model for Teaching Betawi Arts 30 October 2024

- Curricula: Beyond Tradition: Lenong Revitalisation as a Model for Teaching Betawi Cultural Arts 30 October 2024

Rethinking young people’s ‘right to participation’: the case of MAP-CTS Project

Written by: Danae Chatzinikoli and Stefania Vindrola.

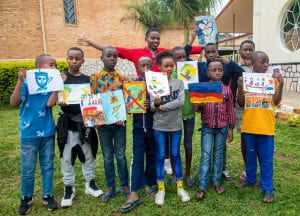

Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP) and Changing the Story (CTS) hosted a three-day conference from 5 – 7 August in collaboration with the Institute of Research and Dialogue for Peace (IRDP) in Rwanda. The conference focused on encouraging child and youth participation through arts-based methods to inform policy and decision-making. It was an opportunity for MAP facilitators, master trainers, policymakers, organisations, partners and participants from Rwanda, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, the United Kingdom and other countries, to interact through both physical and online spaces.

While attending, the concept of ‘participation’ took many different forms. As in most conferences, one could participate by observing, actively participating or both. But due to the new reality that Covid-19 has imposed, alternative ways of participating were introduced. This conference had people participating by being in the conference rooms practicing social distancing, but it also had most of its participants, actively participating from their spaces all around the world online. Time-zones, connectivity and distances were merged into this event. Talks were delivered online from many different places and discussions were made between people who were on opposite sides of the planet. That surely changes the concept of participation and respects the ‘right to participate’ in a different manner. Under normal circumstances, the right to participate would be respected by allowing anyone relevant wishing to participate. Having a specific location for the event would exclude anyone who was not geographically available; therefore, keeping the event limited to people already at the location or those able to travel there. Of course, that creates other types of inequalities in terms of connectivity. Not everyone has access to the internet, and not everyone has a device they can use at any time. But what worked really well for this specific event is that it was hybrid, by having participants both online and in person. It allowed anyone from anywhere to participate eliminating any spatial difficulties that would otherwise limit them. Equally, it allowed young people in Rwanda – who would potentially have had connectivity issues due to a low internet access – to be involved directly. Therefore, the MAP-CTS event was able to equally promote the ‘right to participation’ going beyond social differences that might affect it.

Despite social distancing measures and restrictions, the conference allowed young people to voice their opinions and suggestions in relation to social issues in Rwandan society. It offered them a space to be, act and feel as citizens and exercise their right to participate and be heard. This is remarkable because young people are often perceived as ‘not-yet-adults’: individuals who have not yet developed the competency, rationality and maturity of adults (Uprichard, 2008). As a result, their ideas and opinions do not receive the attention they deserve. The MAP – CTS conference was structured in a way that promoted youth participation throughout the three days. Every session included moments for young people to express their thoughts and answer questions from policymakers and other attendees. Furthermore, their feelings and ideas – represented in a theatre presentation they performed – were the starting point for further group discussions. Throughout the event, young people were involved as much (if not even more) as adult participants. This reflects that, within the MAP-CTS Project, the right to participate is not ‘given’ to young people but otherwise is constructed on the basis of horizontal relations with adults. According to Lundy (2007), children’s right to participate should be guaranteed in a safe and inclusive space, and with adults that listen (not just hear) actively to their voices. This was clear during the MAP-CTS conference not only because of the high youth participation rate, but also because of the inclusion of a diverse range of participants from different ages, gender and school levels. Moreover, the right to participate was not an imposition from adults; during the group discussions young people were always asked if they would be willing to express their opinion as a way to show them it was entirely their decision and that it was safe to do it.

The MAP – CTS Project encourages children and young people to realise that they can and have the right to participate in broader society. This will motivate them to raise their voices with more impetus and strength, but will also have a significant impact on the way they are conceptualised by other generations. The Project goes beyond common stereotypes that tend to consider young people as irresponsible individuals who always get in trouble and cannot control their actions and emotions (Brown, 2009). It contributes to changing the image we have about them and positions them as valuable contributors and shapers of society. For example, one of the aims of the MAP – CTS Project is to connect young people with policy-makers through art-based methods. By doing that, the ‘right to participate’ is again respected in multiple ways. Firstly, young people have the opportunity to participate in a project that allows them to practice their right. Within the project and its workshops, the young people are trained and then train other people in the arts-based methodology. The methodology acts as a tool to reach the next step of the project which is the promotion of peace-building and constructive change. Through the process of being trained and then potentially training others, young people claim their right to participate. There is not some authority that allows them to do so, the training and learning is the enabler in the specific context.

MAP – CTS Project bridges childhood and youth with the policy-making arena. This is an interesting connection because, in the public discourse, political debates and policy-making are activities usually restricted to adults. The Project opens new possibilities for young people and extends their right to participate from their inner realities (family and school) towards their local contexts more broadly. Young people’s views are the pillar of the Project, the reason that connects adults, teachers and policy-makers, and enables them to construct relations with the aim of fostering social changes. In this sense, MAP-CTS promotes a ‘right to participation’ that goes beyond a tokenistic approach and takes young people’s views seriously (Lundy, 2018). Additionally, the Project allows children and young people to understand how policy-making works, how policy documents are created and enacted by different social actors. Therefore, apart from its goal of connecting young people and policy-makers through arts-based methods, MAP – CTS is also a way for the former to learn how society functions every day.

Through this short analysis, it becomes clear that the MAP-CTS Project contributes to rethinking young people’s ‘right to participation’. It does so both by its structure and practically. This specific event can be thought of as a paradigm of how this Project respects children’s and young people’s ‘right to participate’ and of how the response to Covid-19 can create new paths to thinking about participation.

References

Brown, K. (2009). Children as Problems, Problems of Children. In Qvortrup, J., Corsaro, W. & Honig, M-S. (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies (pp. 256 – 272). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927 – 942.

Lundy, L. (2018). In defence of ‘tokenism’? Implementing children’s right to participate in collective decision-making. Childhood, 25(3), 340 – 354.

Uprichard, E. (2008). Children as ‘Being and Becomings’: Children, Childhood, Temporality. Children & Society, 22, 303 – 313.