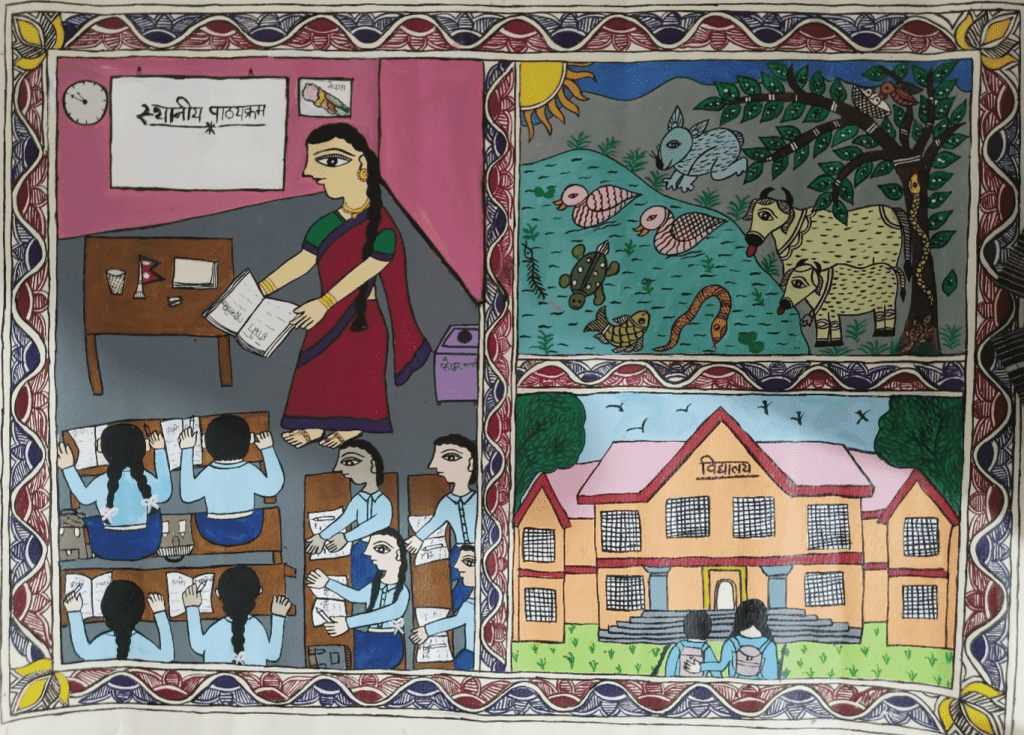

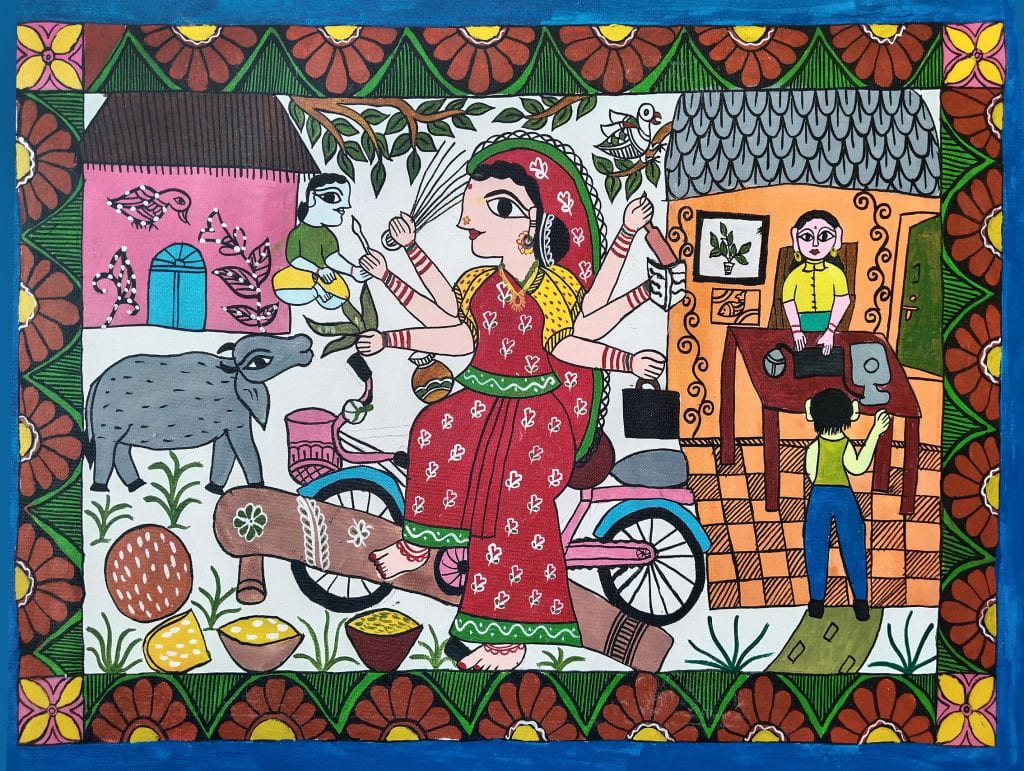

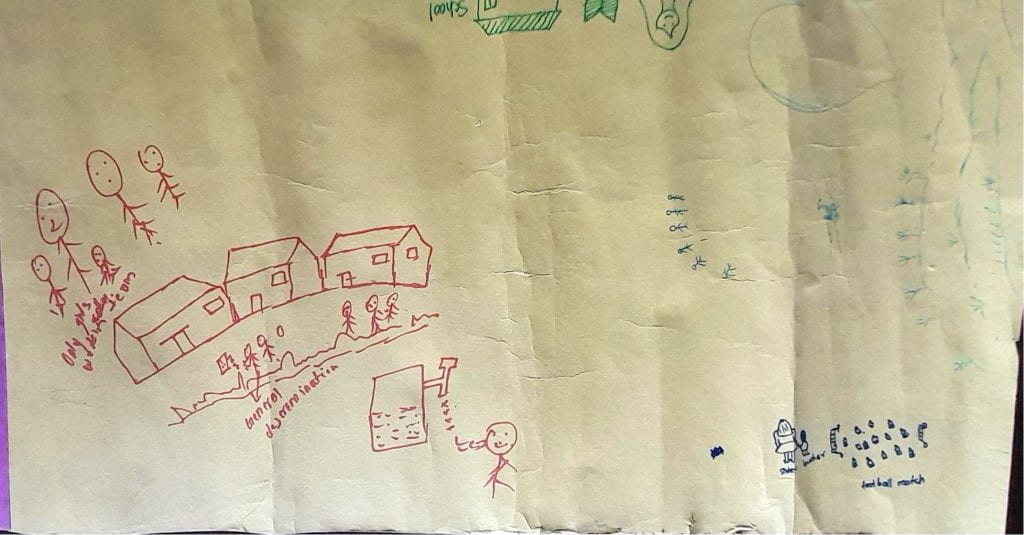

Implementing the Emancipated Curriculum in Indonesia, which has replaced the 2013 Curriculum (K13) in secondary schools, has several challenges. Among them is the absence of a standard textbook. Whilst this is not enforced by the Emancipated Curriculum, schools still hope for guidance. Another challenge is that teaching staff are overwhelmed with the legacy of the…

Press: Art-based Pedagogy for the freedom of thought and creativity: an alternative approach to implement the Emancipated Curriculum in Indonesia